apan’s big bet on stem-cell therapies might soon pay off with medical breakthroughs

Japan is brimming with signs of an approaching medical revolution. Shiny white robots are tending dishes of cells, rows of incubators hum in new facilities, and a deluxe, plush-carpeted hospital is getting ready to welcome its first patients.

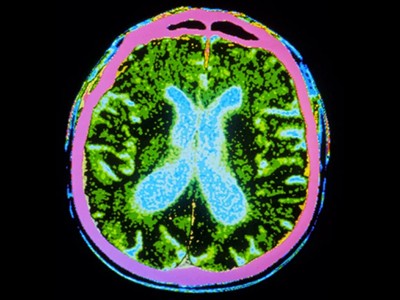

Building on the Nobel-prizewinning work of stem-cell scientist Shinya Yamanaka, researchers across the country are crafting cells into strips of retina, sheets of cardiac muscle or blobs of neurons, in the hope of treating blindness, mending hearts and reversing neurodegeneration. Results from early-stage clinical trials — some announced just in the past few weeks — suggest that the cells might actually be working to treat conditions as varied as Parkinson’s disease and spinal-cord injury.‘Big leap’ for Parkinson’s treatment: symptoms improve in stem-cells trials

Now, after nearly two decades of hard work and setbacks, many say that Japan is on the cusp of bringing these therapies to market.

Yamanaka, who runs a lab at Kyoto University, discovered in 2006 that adult cells could be reprogrammed into an embryonic-like state, capable of becoming practically any kind of tissue1. These induced pluripotent stem cells — or iPS cells — won Yamanaka the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2012, and propelled him to superstar status. They have become a symbol of the country’s global scientific aspirations.

The Japanese government has poured more than ¥110 billion (US$760 million today) into research and development on regenerative medicine, on top of billions more from private funders, organizations and companies. “People thought, ‘Now we can treat any incurable disease’,” says Shigeto Shimmura, director of Fujita Health University Haneda Clinic. “There was so much hype.”

Scientists launched clinical trials and start-up firms. Large biotech companies swooped in, investing even more in manufacturing hubs. Now, medical facilities are preparing to welcome a rush of patients from Japan and abroad. “Regenerative medicine in Japan is moving very dramatically,” says Masayo Takahashi, an ophthalmologist at Kobe City Eye Hospital and president of the biotechnology company, Vision Care. In 2014, she became the first to treat someone with cells derived from iPS cells.

There are more than 60 iPS-cell clinical trials in progress worldwide, nearly one-third of them in Japan. The treatments have proved to be safe and shown signs of benefit. Moreover, the technology has been improving apace, says Shimmura. And thanks to a fast-track approvals process for regenerative medicine, Japan could become the first country to approve iPS-cell-based treatments. This could happen within a year for Parkinson’s disease.

But those approvals are not yet in hand, treatment costs are high, large trials showing clear clinical benefit have yet to materialize, and concerns about safety could still sap the public’s willingness to try this treatment. “We’re down to realizing what the potential of these cells are, and what the limits are,” Shimmura says.

Eye see

Yamanaka’s iPS cells promised to bypass a bioethical stand-off that had threatened the potential of embryonic stem cells for a decade. Because production of iPS cells doesn’t require the destruction of human embryos, they were considered ethically less fraught. Furthermore, because they could be made from the cells of the person in need of treatment, they promised to offer transplantable tissues without the need for immune-suppressing drugs.

In 2014, Takahashi put this idea to the test. She took skin cells from a 70-year-old woman with a progressive eye condition known as macular degeneration and guided them into a younger, more pliable state using a recipe similar to the one Yamanaka had devised and refined. The resulting iPS cells were then grown into thin sheets of retinal cells and transplanted into the woman’s eye, where they have survived for ten years and prevented further vision loss, Takahashi says.

It was a procedure with practical limitations, however. Self-derived, or ‘autologous’, cell therapies are time-consuming and expensive to make, and the large cell-sheets that researchers crafted for implantation required intrusive surgery. Takahashi says she chose this approach to ensure the highest chance of clinical benefit — to demonstrate to the world what was possible. It was designed to be “scientifically, the best treatment”.

But Takahashi wanted to create a commercially viable treatment. This meant a change in approach, using cells from donors that could be mass-produced, and finding less invasive ways of getting them into the eye.

hi